|

Thomas

Kretschmann |

AboutFilm:

You must be very happy with this film.

Kretschmann: Very happy. Yeah.

I wasn't expecting anything, because, clearly the part wasn't that exposed

in the script, and even though Polanski came to me and said, "For me this

is the most important part except the Szpilman part," I was just happy

to shoot with him. When I read the script, for me it was clear this is

probably a film he was waiting for his whole life, because it's so similar

to his own story.

AboutFilm: Why do you think he came

to you for this role?

Kretschmann: Well, he didn't really

come to me. I knew about the film, and I called the casting director,

and I said, "I want to have a shot here." And she said, "He doesn't meet

people. He doesn't look at photos, because he thinks everybody looks always

different. He looks at tapes. So I make tapes of different actors." I

said, "Okay, I want to do that." But know how it is, they put the video

recorder on--"Good morning, Kretschmann." [laughs] You know what

I mean. You're sitting there, and you say, "Hi, I'm Thomas Kretschmann.

I am… I am… what?" You're sitting there thinking, "This is so stupid."

So I read some dialogue out of the script. He's saying this and this,

and I'm saying this and this, and he's saying this and this, and I'm saying

this and this, and that was it. Then I get a phone call from Polanski

two weeks later. He thinks it's great and fantastic, and he has to meet

me right away. We met, and he shakes my hand, and the first thing he said

is, "Do you want to be in my film?" That was it. I got very lucky, because

if I had to audition for the film, I wouldn't have been in it. I fuck

up every audition I do.

AboutFilm: He knows what he wants,

clearly, and is able to identify it.

Kretschmann: Yeah. Later I heard

he thought it was the greatest casting he'd ever seen. [laughs]

Then at the press conference in Cannes, he said, "There was this German

actor who read my script like a telephone book. Like a menu. And I thought

it was unbelievable." When we started shooting, he comes up behind me,

first shot we do, and he says, "You do exactly what you did in casting."

I said, "But I didn't act." He said, "Exactly." He was very obsessed with

not acting, and being real. You can see it in the film. I think the big

power of the film is that you don't have the feeling you're watching actors

acting.

AboutFilm: Well, it is a small role

in terms of screen time, but Polanski's right, it is a critical role,

and it is a role that requires that you carry authority and presence.

Were you conscious of that when you were filming?

Kretschmann: Yeah, I was. But you

know how it is, I do so many films. Mostly you work your ass off, and

everybody tells you it's such an important part, and you work for months

on a film, and then you see the film, and you think, "What happened? What

happened to what I thought was going to be? What happened to what I did?

I don't see anything of it." Here, everything that I did, I see onscreen.

But I wasn't expecting that.

AboutFilm: What were you expecting?

Kretschmann: I wasn't expecting anything.

I'm not expecting anything anymore. For me, the film is over after shooting.

As an actor, to survive mentally, I have to get used to seeing the shooting

as the main event. Being on set is for me the fun part, and the work is

there. To have no wrong or disappointing expectations, just forget about

it afterward.

AboutFilm: Because you have no control

over the final result.

Kretschmann: No, you don't. But you

can see the credits. [Kretschmann's name is above the title with Adrien

Brody's.] I didn't have that in my contract. For Polanski, [my role]

was very important. For me, as a German, what was important was, I was

facing an example of the victims. Polanski stands for the victims. He

was in the ghetto. He saw his mother carried to Auschwitz and never returning,

being gassed by Germans… I am a German. I'm lucky, because I can say my

grandparents were not involved, because my grandfather deserted and took

my family away from there, and he could have been shot for that. But I

feel responsible. What I wanted is, what my major focus was, I wanted

to be with him. I wanted to help him to fulfill his vision. I walked on

set, and thought, "Whatever he wants, I do."

AboutFilm: What does it mean to make

World War Two movies and Holocaust movies like this one or U-571,

as a German? How do you feel about it? What does it mean to you?

Kretschmann: Clearly for a German

it's not so much fun to play a German in the Second World War, or a Nazi.

This is not a Nazi here; also the captain in U-571 was not a Nazi,

he was a soldier. That's a difference not everybody knows. But clearly

it's not so much fun. For an American actor, he doesn't carry this historical

responsibility. For him, it could be great fun to play this character,

because he doesn't have to face his own past, right? But take U-571

for example--with what kind of film [can] I make myself visible to the

audience or to the industry if not this? These are the films people want

to see me for, and these are the films [in which] I can make an acting

statement, and get attention, and be hired for other stuff afterward.

These are the films you have to put your foot in the door... [The Pianist]

is different, in my opinion. It doesn't have anything to do with that.

It's a brilliant director; it's a brilliant script, and as a German, I

am perfect for this part.

AboutFilm: How much did you know

about your character? How much is known about Captain Hosenfeld?

Kretschmann: We know he really existed.

He was a teacher originally, then he was a soldier. He saved numerous

lives, and he died, like it says in film, in '52, in a [Soviet] prison

camp.… There was also, in the book, a diary of him, and you could read

it all. I did, but I figured out that Roman didn't want me to do this

really. The more information I brought into the shooting, the more it

distracted me, and the more it distracted him. Roman didn't want that.

As an actor, you start reading this stuff, and you think, "Oh this is

great, maybe I could put it into my part." Then you come to Roman, and

he goes, "No, no, no." He has his own vision. Then I just dropped it.

Because I figured, it starts me working against him, and I didn't want

that.

AboutFilm: So how did you interpret

and express your character?

Kretschmann: The scene where Szpilman

plays the piano, that was the one scene where I could express the character,

because for the rest of the time, he does what he does. He's not talking

about it. He just does what has to be done. This is the only scene where

you can give the audience an idea how he functions. I tried to put everything

into this, [even though] he's just sitting there, listening. I was just

sitting there thinking, "I have to put the world in it. Everything." It

was eight and a half minutes, and [Polanski] shot it through. In my mind

I tried to go through a whole lifetime of the highest highs and the lowest

lows. [Polanski] did one take, and then he said, "That's it." I was actually

prepared to start working at that point, but he said, "That's it." He

refused to do another take.

AboutFilm: How did Polanski see your

character?

Kretschmann: Up to the point when

my character arrives, you see Germans doing only horrible things, so you

don't expect anything good from Germans, right? So at the point he arrives,

Roman wanted to have it really neutral, not over-exaggerating. [Hosenfeld]

just does what a normal human being would do. [The film] makes him a symbol

of hope, but it the end, he's just doing a regular thing. He did risk

his life, of course; he was probably a great man. He stood up for his

belief. In this way I kind of connected with him, because I escaped from

[the former communist] East Germany. In East Germany, you had three possibilities.

You go with the system and sacrifice your ideals, and live how the system

expects you to live. Or you go against the system, and you're going to

be fucked for the rest of your life. Or you escape. I escaped.

AboutFilm: How did you escape?

Kretschmann: I ran over the border

in 1983. I was nineteen. My mother was in the Communist Party, and she

was the principal of a school, so she wasn't very happy. I went to Hungary.

If you went [directly] from East Germany to West Germany, you pretty much

[ended up] dead or in jail. It was stupid to do that. They also had mines--you

just walk on one, and that's it. But you could go to Hungary. I went running

over the border to Yugoslavia, and then Austria. There they shoot you,

too, if they can, but at least you don't step on a mine or something.

If they shoot at you, you can react at least.

AboutFilm: Before that, you used

to be on the national swimming team?

Kretschmann: I was on the East German

national team, yes. I started swimming when I was six. When I was ten,

I was asked if I want to be world champion, and when you're ten years

old, you say, "Yeah, sure." And then you're in the system. I swam twenty

kilometers a day. When I was eleven, I swum--by accident, because it was

not even my major thing--the 1500 freestyle, I broke the German record

for that age by far, so then I was locked into the Olympic program. They

had a strategy to push you where you're supposed to go. When I was fourteen,

I had enough already, mentally, because I saw all the other children having

a childhood. And also I figured out my hands are actually too small, and

I lost interest. I dropped out when I was seventeen. When I stopped swimming,

I started acting school. I dropped out immediately, because I was surrounded

by great 'feelers'--everybody was 'feeling'--and I felt like I was in

psychotherapy. So I never learned acting. I thought, "This is not what

I think it's supposed to be." Then I went to the National Theater in Berlin,

and I did an audition there, and they took me. I didn't tell them I didn't

do any acting school. Actually I told them that I did.

AboutFilm: Was there anything about

the survival story that resonated for you personally, since you had been

through an escape experience yourself?

Kretschmann: Well, I don't know.

Roman Polanski is Polish; I am from East Germany, maybe we clicked there…

Growing up in different environments politically and leaving them because

you believe in self-responsibility. Maybe, without talking about it, that

unified us. From the first minute I met him, I kind of had the feeling

I understood him. Also, as an East German, we grew up thinking about [the

Holocaust], because they hammered it in your head. The East Germans have

been actually very responsible [about] their past. They taught it, with

the Russians being the big brother, you know. We visited concentration

camps. We grew up with, "We are part of the guilty nation for the biggest

misery in the world." So, you have the feeling you know everything about

the time. But, when you see the film, you see you don't know anything.

If you're in the middle of it, you're speechless.

AboutFilm: How many days did you

work on the film, and how much did you work with Adrien Brody?

Kretschmann: I didn't work long on

the film. Just two weeks. The difficult thing, not for me, but for Adrien

was that, for practical reasons, we started shooting the film with these

scenes. I think that's a great achievement for him as actor, how perfectly

he became this person. With Adrien, we worked on our dialogue because

he had to speak German with me, and he did an amazing job, actually. He

sounded like my grandmother--not the voice, but the tone. My grandmother

is from Poland. It was creepy. We didn't rehearse very much, but we worked

on that.

AboutFilm: Let's talk a little bit

more about Polanski, if you don't mind. He remains a bit of an enigmatic

figure here, obviously because he left twenty-five years ago. He has been

an actor himself. Do you think that influences him as a director?

Kretschmann: Yeah, totally. He didn't

want to dictate what you have to do. There was one thing he wanted--simplicity.

That's what he said all the time. We didn't talk very much about the character.

We didn't rehearse very much. We didn't have big meetings. Nothing like

that. It was obvious to me the film was in his head already. So he walks

around on set, and he's involved in every detail of what's going on. In

between, he takes you around the corner in the next room, and he goes,

"Say these lines for me." Then you say the lines, and he listens, and

then he's mumbling the lines. But he's not doing it like, "Look at what

I'm doing." He's just trying what he would do, and you watch him. Then

you do it, and he watches you. It's kind of like a conspiracy… can you

say? You are observing each other. He never said, "Do it like this." He

was with you, and had you try it this way and that way, and tried it himself,

and then you walk on set and you do it. When we did the first shot, he

had me do seventeen takes. As an actor, after ten takes, you start worrying

about your ability to do what [a director] wants you to do. And then he'll

print the first take and the third. But I knew he was testing me. He wanted

to know that I would go with him all the way. After that shot, he did

only one take, two takes, three takes, that's it.

AboutFilm: So then, it was a very

naturalistic approach. You say the lines a few times, you refine them,

you go on set and you recite them. It's not hours and hours of trying

to put yourself in your character's shoes.

Kretschmann: No, no. It was very

light--everything, the whole process. Also, if you have the chance to

meet with Polanski on set, you want to know things. I tried the whole

time to get information out of him, out of his own experiences. He was

very closed. He didn't talk very much about himself; he didn't talk very

much about the scenes. He wanted you to be a part of it, but he didn't

want to take the whole thing apart. He just went with you around the corner

and played around with the lines a little. Then after the film was done,

he opened up. He took me to the first [screening]. Afterwards he says,

"This scene happened to me. This scene I watched. This scene…" You get

the feeling that the whole thing is packed with stuff out of his own life.

But he didn't let you know. I think he didn't want to be distracted. He

said all the time, "Concentration is my big passion. I need concentration!

I need concentration!"

AboutFilm: You're talking as though

you worked by closely reflecting Polanski's desires in this film. Have

you worked with other directors in that way?

Kretschmann: Yeah, I worked with

Patrice Chéreau in that way [in La Reine Margot]… [pauses]

I've done fifty films. I've worked with many directors, good ones and

bad ones. So if I have a chance to work the good ones, I better put myself

in their hands, and trust them, because that's my big opportunity to be

different, and to be better than usual. It's not a big deal to face a

director and know, "This is going to be bullshit; I better save my ass

here." I can do that. But if you have a chance to work with somebody like

[Polanski], you just want to go with him, and hope he gets something out

of you that nobody could before.

AboutFilm: So if you work with a

bad director, what do you do?

Kretschmann: You get the feeling

if the film goes downhill, or if it doesn't work. But you're in it already,

so the only thing you can do is save your scenes, save your character.

Best scenario, the film comes out, and people say, "The film was shit.

Kretschmann was good." You have to fight for that. You always want to

be with your director, but sometimes you don't have the choice.

AboutFilm: What's it like acting

under a lot of make-up, like in Blade 2?

Kretschmann: Well, the process was

horrible, because it was about seven hours of make-up. After walking out

of make-up, you're already done. You're exhausted; you want to go home.

Then you go on for another six or seven hours acting. That's horrible.

I never want to do that again. It's like masochism, to put this shit on

your face. But, underneath, [aside from] the pain, and the sweating underneath,

and the burning everywhere, and itching--except that, the acting is fantastic.

You can do whatever you want, because it's not too much. You can allow

yourself to do whatever you want, you're not ashamed. For the character,

everything is possible. It reminded me of theater. You can scream and

spin around and move around like an idiot, exaggerating, and it's right.

There are totally different laws, and it's fun for that. It's absolutely

fun. But the pain… not again.

AboutFilm: I understand you are making

another submarine movie, U-Boat, to be released in 2003?

Kretschmann: Yeah. We just finished

that two weeks ago, with William H. Macy, Scott Caan, Til Schweiger, and

myself. The director [Tony Giglio] came to me with the script, and it

was fantastic. In U-571, I didn't have so many opportunities, you

know? Everything I couldn't do then was in this script. Plus, the director

said, "I want to do kind of an art-house U-Boat film, European style.

A drama in a U-Boat." It's about Americans and Germans who stick together,

and go home. Fuck the war. I liked the script and the director so much,

so that's why I did it.

AboutFilm: You now live in Los Angeles.

I was recently interviewing your countryman, Moritz Bleibtreu [Run

Lola Run, Das Experiment],

who said he was interested in working in English-language movies, but

that he didn't see himself making a big career here because foreigners

will always trouble getting roles that aren't specifically foreign. So

he said he'll always be living in Germany and working in Germany. Yet

you live here, which suggests you don't agree with that. What's the difference

for you?

Kretschmann: Well, I don't see a

film industry in Germany. They have a great TV culture…. but how many

German films are really exciting? Let's talk in the last ten years. There's

not much. For me it was clear. I did a film in '92 called Stalingrad--it

was a very big film for Germany. After that film, I thought, "It doesn't

get any bigger here. I have to leave." That's also part of my ego… I was

a competitive swimmer. So this is part of what I am. I want to play with

the big boys. I don't want to sit there at seventy in Germany, and think,

"I probably had the craft as an actor to do those great films, but I never

made myself available." You have to come here. Polanski gave me [the name

of a] really good dialogue coach here, Julie Adams. So that's what I'm

working on now. I want to try it out. And if I fail, I fail, but I can

look at myself in the mirror and say, "I failed, but I tried."

AboutFilm: Going back to The Pianist,

what do you hope for this movie? Maybe it will get a big theatrical release

everywhere in the country, but I don't know. What do you see happening?

Kretschmann: I guess it will. I think

it would be a shame if not. There are each year so many blockbusters--big

audience, big release--and you can be part of it or not, and it doesn't

make a difference really. You forget [them] already two months later.

This is a film that stays, I believe. This is a film that's going to be

around in fifty years, probably in a hundred years, if the world is around

in a hundred years. [laughs] I'm sure that when I'm eighty and

I'm sitting with my grandchildren, I can show them this film. I can be

proud of it. This film will still make sense, and it will still matter…

I think it's going to be a classic. It's such a true film. You walk out,

and you don't have the feeling you watched a film, you have the feeling

you've been in the middle of it. The film grabs you.

AboutFilm: I think it succeeds because

it doesn't try to be about to much. It's very specific. It's about a specific

individual, and often the greatest truths can be found in those little

things, I think. Whereas a movie that sets out to be about all aspects

of the war, or the Holocaust, that's over-ambitious. Oftentimes those

movies fail, I would say.

Kretschmann: Oh absolutely. And I

think that the great quality about the film is that it's not whiny. What

makes it so tough to watch is that the camera doesn't go, "Look how horrible,

look how miserable." The camera just walks through this stuff. This is

happening, and this is life. It's about life surviving where it has no

way to survive. Roman always says this film is about hope. It's very difficult

to understand that, but it is. It's about going on. It's about life.

|

|

|

Adrien

Brody |

Question:

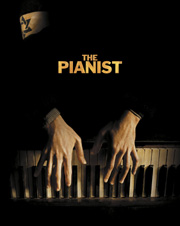

In The Pianist, we see hands playing and then the camera pans up

and it looks like it's actually you. Do you play the piano?

Brody: I had to learn to play the

piano for the film. I do have a basic knowledge of piano. I've studied

off and on for years, but I'm definitely not a concert pianist. I had

to learn to play a portion of Chopin's Ballade No. 1--a really

complex work--in a very short period of time. I had six weeks.

Question: In the scene with the German

officer [played by Thomas Kretschmann], that's you playing the whole piece?

Brody: Early on it is. That's Ballade

No. 1. That's what I had to practice for. And that was the first week

[of shooting]. I had six weeks before we started. I went down to 130 pounds,

and I had to play that. That's what [Roman Polanski] required. It was

important that I knew to play because it was important to Roman that he

could actually use me playing. It's not just a cut to me, or a cut to

the hands. He wanted, first and foremost, to know that I would be very

dedicated and disciplined. I had to be. There were no options. Within

those six weeks I had to lose a tremendous amount of weight; I had to

grow that beard; I had to work on a dialect, and I had to learn to play

the piano. I had a six month movie in front me, and I was starving myself

and having four hours of piano a day. I was immersed in it. It was a lot.

It was more than I've ever had to do, and I had to stay in this space

for a really long time.

Question: In the credits, they credit

somebody else with being the piano player.

Brody: Well, yeah. Obviously there's

no way that I could play [on the soundtrack]--you couldn't expect that.

But I still had to play it. Not only did I have to play it, and play it

with a style that was played then, but I had to play at the pace that

they were playing it. It's like you're lip synching, but really singing.

Because you have to hit the right notes, and you are playing. It's

a complicated procedure. Already it was tremendously difficult because

I don't read music very well, so I learned on memory, which took constant

practicing. Once I was able to play well, I would play in time with the

music they were going to use… But yeah, [Janusz] Olejniczak is a phenomenal

Polish pianist who did the interpretation of the music for the film and

would play those long stretches that were way too intricate. I mean, these

are like Olympic pieces, and I'm a novice.

Question: Were you ever absolutely

exhausted?

Brody: I was exhausted from Day One.

Day One, I had to climb over [a] wall and witness the destruction of Warsaw.

I had been confined to my room, just working on the things I've been describing.

I had no energy. I hadn't eaten much. I hadn't eaten that day; I hadn't

eaten much for six weeks. I had no energy, and I told Roman that

I had no energy. He said [in Polish accent], "What do you need

energy for? You just do it."

AboutFilm: That must actually have

been ideal.

Brody: That was ideal, because,

first of all, I connected immediately, psychologically, to this state

of isolation and deprivation that my character had. At that point I was

completely changed, already, and that was Day One. I could barely climb

over that wall. They were doing a complicated crane shot; I had to do

it a few times; it was freezing, and I could barely make it over this

wall. My muscles were gone. That's what Roman wanted. And in retrospect,

I'm okay. I made it through it. Probably it could have been harmful, but

I'm fine today. And I felt that I had a responsibility in my portrayal

of this character, and that I had to do it as honestly as I could. I think

Roman felt that I was willing to give him that in the casting process…

Before I left home I gave up my apartment in New York, sold my car, and

got rid of my phones, because I thought, "Hey, this character loses everything,

why don't I be very dedicated and do this?" When I got there, I was like,

"That was really stupid, I didn't need to do that because I'm already

going to go through hell here, and it would be nice to have a place to

think about." But I felt like I shouldn't have a place that I could call

home.

Question: What kind of food and diet

were you on before you started the production?

Brody: Oh… I had two boiled eggs,

and then I didn't have anything for about five hours, and I had a small

piece of chicken, grilled, under 200 grams. Dinner was four or five hours

later, and that would be a small piece of fish and a few steamed vegetables,

and that's all I ate.

Question: How much do you weigh now?

Brody: I'm about 155, but I was about

160 when I started [preparing for The Pianist].

Question: How did you get involved?

Brody: I got a phone call out of

the blue that Roman wanted to take a meeting with me. I was shooting Affair

of the Necklace in Paris, and I got this call. I was like, "Oh yeah!

Okay, whenever, wherever." We met and had coffee, and talked about it.

He got a script to me. Then I invited him to see a screening of Harrison's

Flowers, and he came with a producer, and went out for a beer with

me afterwards. I took that as a good sign. We talked about the script,

what my intentions would be, at what level I was committed, if I had some

knowledge of music. It was a long process, but he never made me audition.

I really appreciate that, because this is a role I would die to get an

opportunity to audition for. I know he saw a lot of people for it, and

I know there were a lot of incentives to hire a European actor, and for

some reason he chose me. It's kind of the break that I've been looking

for, for a really long time, and he gave it to me. I love the guy for

that. He gave me a lot of respect. I've had to audition for things that

are effortless for me, and I have plenty of tape that they check out,

but there's something about that process. Some people need you to prove

your work, and that's what actors have to do constantly. But he had some

faith in me, which is really wonderful.

AboutFilm: You said that Polanski

told you to just do it. Was that characteristic of the direction you received?

Brody: Oh no, it was far more intricate

than that, complex and specific at times.

AboutFilm: Could you talk about that

process?

Brody: Well, Roman has a very clear

vision in his work, and I have faith in him and trust him to guide me.

He strives for subtlety, and so do I. You have to be malleable, but if

you have a director who strives to guide you in a similar direction, then

that's a real luxury. It was a fascinating process, because he's experienced

a lot of similarities and a lot of suffering in his life. He survived

Krakow through that time. Not only did I have a director that I admire

and that I'm confident in, but he knows what my character went

through. He also possesses a strength that I felt my character had to

have had in order to survive all that. It was a phenomenal opportunity

for me to have a director who I admire and the guidance of someone who

shared parallels with the person I was actually portraying.

Question: The order of shooting is

very interesting, in that you started at a very extreme point. You started

from the place where Szpilman evolved to, and then you went back to the

earlier place, where he was a confident, well-respected guy, not ever

imagining what could possibly happen.

Brody: Right. In retrospect, I think

I could only have interpreted it as clearly because we shot in

reverse. It allowed me insight into this man and that place. It's far

more difficult to read an individual whose life is in order, who's apparently

very normal. There's only so much information given. [Szpilman] is not

particularly religious. He has an opportunity for love but he's not deeply

in love. He's passionate about music, but… it's hard to jump into that.

But I became immersed in [his later] state of mind, knowing what he's

capable of enduring. You know him and where he went, so you know what

to work away from, and the trick is to slowly shed it. It's difficult

to shed it, but you have to try to peel off these things that you've developed.

It was a long process. Six months, six days a week, every day, is a long

shoot to say the least. There was a month and a half when there wasn't

even another actor on the set. That was a fantastic opportunity, because

you've got Roman and a crew at your disposal, and all this focus on your

character's journey. That's fantastic. The flip side is, there's not a

window to let go. And if you can't let go for long enough, you somehow

change… And Roman encouraged the isolation. He communicated with the crew

in Polish, partially out of necessity, but there's no other actor there.

He didn't need to tell me much… I'm a starving man sitting in a room,

what am I gonna do? Until he needed to say something to me, he wouldn't.

I'd be in my trailer, practicing the piano, come back out, do my scene.

Question: After going through Szpilman's

life, do you appreciate more your own life?

Brody: Absolutely. It put so much

into perspective for me that I can't even tell you how I would feel today

without this experience. Hopefully it'll do that for people who see the

film, just getting a glimpse of what kind of suffering one individual

endures, and how fortunate we are not to go through that. Even on a simple

level, it's made me appreciate being able to eat, being able to be with

friends, having shelter. These are things that I have taken for granted,

and that we all take for granted. It's human nature to complain--and it's

legitimate, because we all want to strive to have better things and be

better people and grow--but, you have to remember your own good fortune,

and you have to be aware of other people's misfortune.

Question: Was there any specific

moment in the story that stood with you, that revealed something about

the character to you?

Brody: There was one specific thing

that seemed particularly tragic, not the horror, death, and everything,

but when he was locked alone [inside an apartment]. There's a piano there,

and he couldn't play. I didn't get it in the memoirs; I didn't get in

the script, but then I was locked in the room with this piano. I had been

playing a lot, so when I see a piano, I go to play it, because it brought

me comfort, too. I also identified with the music, because I omitted all

the modern music from my life, and I just listened to that kind of music.

Being able to play music, and having some control over it, you understand

the story behind the music, and the connection between the composer or

the pianist and the work. I felt a closeness to this piano now. I couldn't

touch it. It was like being locked in a room with your loved one, and

being unable to touch. It was profoundly tragic for me in that moment.

Question: What was your favorite

sequence in this movie?

Brody: I think when I meet up with

the German officer at the end, and I have found [a can of] pickles. There's

some hopeful element, and he's at his lowest point, and there's some interaction

all of a sudden with a human being. It was moving, really moving for me

doing it. When [the officer] brought me bread in that scene, in the first

take or something, I cried, because I smelled the bread. I hadn't had

any--any!--carbohydrates. A-ny. Period. It was this loaf of real

bread, baked bread, Eastern European thick hearty bread, and I just thought,

"What must this man feel, getting a loaf of bread from a Nazi officer

instead of a bullet in the head?" It made me cry. And he was probably

more way more hungry than I could have ever imagined. And I couldn't

have gone there without all this other stuff that Roman guided me into.

It was really profound. That's what I want to get from my work. That is

the beauty of acting, when you can connect with these things, and hopefully

transmit these emotions to people, and gain something. That's how you

benefit. I mean, doing a fun character that's entertaining is great. There's

nothing wrong with it. But it's far less enriching.

Question: Did Polanski ever discuss

his personal experiences with you?

Brody: Absolutely. He shared a lot,

and it was invaluable. He incorporated a number of things into the film

that he had seen [himself]. For instance, the woman who is shot by a German

officer and she falls on her face in that strange contorted position.

He saw that as a boy. It struck him, and he was so specific about how

she fell. He laid in the dirt to show her how he wanted her to fall. You

have a director, Roman Polanski, laying in the ground to show an extra

how to fall. That's really inspirational, because he's that involved,

and he cares that much about it. It helps.

Question: What are you going to do

after this?

Brody: I don't know. I don't know.

Hopefully it will inspire people to send me some good material. I'm very

selective. It's hard to find something that tops this. You can't say,

"Well, what's going to take me to the next level?" because… creatively,

this was pretty profound for me. I don't expect everything to be that

way. But I do need something that will provide me some kind of growth

in another way. I would love to do something with some romantic involvement,

some serious leading man with a wonderful woman who's a fantastic actor…

contemporary stuff that's real, and powerful, and moving. That's where

I'm at. I'm ready for that kind of material.

Roman

Polanski and Adrien

Brody on the set of The Pianist.

|

Roman

Polanski and Thomas

Kretschmann on the set of The Pianist.

|

Roman

Polanski on the

set of The Pianist.

|

|