| Eyes Wide Shut |

| |

|

USA/UK, 1999. Rated R. 159 minutes.

Cast:

Tom Cruise, Nicole Kidman, Sydney Pollack, Marie Richardson, Sky Dumont,

Todd Field, Vinessa Shaw, Thomas Gibson, Rade Sherbedgia, Alan Cumming,

Julienne Davis, Leelee Sobieski

Writers: Stanley Kubrick and Frederic Raphael based loosely on

Traumnovelle, by Arthur Schnitzler

Music: Jocelyn Pook

Cinematographer: Larry Smith

Producer: Stanley Kubrick

Director: Stanley Kubrick

LINKS

|

Note: The review contains no spoilers. The analysis

contains spoilers and is intended for readers who have already seen the

movie.

Review

dreamlike,

slow-paced sucker-punch to the mind, Eyes Wide Shut is in many ways a

typical Stanley Kubrick film. Lush but detached cinematography, fantasy blurred

with reality, leisurely narrative, a protagonist driven to the edge of dementia–all

are hallmarks of Kubrick's work, and, like in so many other Kubrick films, the

moments of brilliance in Eyes Wide Shut more than make up for the times

Kubrick loses his way.

dreamlike,

slow-paced sucker-punch to the mind, Eyes Wide Shut is in many ways a

typical Stanley Kubrick film. Lush but detached cinematography, fantasy blurred

with reality, leisurely narrative, a protagonist driven to the edge of dementia–all

are hallmarks of Kubrick's work, and, like in so many other Kubrick films, the

moments of brilliance in Eyes Wide Shut more than make up for the times

Kubrick loses his way.

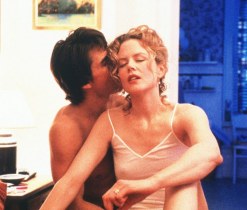

Eyes Wide Shut concerns a privileged doctor, Bill Harford (Tom Cruise),

and his journey through a seamy underworld of illicit sex and crime. When Harford’s

wife Alice (Nicole Kidman) confesses to having fantasies about other men, Harford

begins to question things he once took for granted, like Alice’s loyalty and

love, and women’s attitudes in general toward sex. Driven to seek answers to

these questions, Harford becomes obsessed with lust and carnality.

Eyes Wide Shut is best described as an intellectual art film. The advertising

hype is that Eyes Wide Shut is an erotic thriller replete with steamy

sex. The truth is that, although there is plenty of sex and nudity, very little

of it is erotic. For this reason, the word of mouth on Eyes Wide Shut

has been terrible. Indeed, if you’re looking for escapist entertainment, you

won't find it here. But if you’re willing to keep your mind wide open, you may

be richly rewarded. Like many other people, I walked out of this movie disoriented

and unsure of what to think. I didn’t know whether Kubrick’s swan song was a

masterpiece or a pretentious mess. But I couldn’t get the movie out of my head

for days. The more I assimilated it, the more I realized that everything in

the film, even elements that at first seem clumsy or flawed, is in fact meticulously

planned. Everything serves a purpose.

Eyes Wide Shut may be Kubrick’s most intensely personal film, and thus

your enjoyment of the film will depend on your ability to relate to Kubrick’s

thoughts and feelings. Kubrick’s notions about sex have been accused of being

quaint and out-of-date. Perhaps. Eyes Wide Shut is certainly not a modern

film (it would have been far more effective had it been set before the sexual

revolution), but the sexual stereotypes it explores continue to exist today.

That being said, Eyes Wide Shut does have problems, particularly with

narrative flow. Rather than one event leading smoothly and logically to the

next, the story drifts fitfully to its abrupt conclusion. Many audiences have

found the movie to be boring as a result.

There has been much publicity surrounding the alteration of an orgy scene in

the U.S. version of Eyes Wide Shut, during which couples having sex are

obscured by digitally inserted figures. The digital manipulation should be patently

obvious even to viewers who do not know to look for it. The figures are too

obviously placed in strategic positions, and Dr. Harford, from whose point of

view the scene is shot, makes no effort to see past the obstructions–a big clue

that they’re not supposed to be there. Eyes Wide Shut would have earned

an NC-17 rating without the digital changes. Meanwhile, if those same couples

were shown chopping each other to small pieces with large machetes, the movie

would have had no trouble earning an R rating. Our society’s taboos are frighteningly

misplaced.

It’s interesting how, in its uneven brilliance, Eyes Wide Shut is similar

to another recent movie by a reclusive eccentric not heard from in years, The

Thin Red Line. Whereas the brilliant moments in The Thin Red Line

were few and far between, and the film was largely incoherent, Eyes Wide

Shut comes much closer to being a masterpiece. Though it probably is not,

sometimes you feel like you are watching one. That's worth the price of admission.

Analysis (contains

spoilers)

I hope I don’t

offend the gods of cinema by pointing out that [the] somber control-freak orgy,

as perversely spellbinding as it is, isn’t really sexy.

–Owen Gleiberman, Entertainment

Weekly

Stanley Kubrick's 13th and last film is...empty

of heat.... Frankly, it's the dullest orgy ever seen.

–Stephen Hunter, The Washington

Post

It's shocking only in its banality, impotence and

utter lack of heat–this, despite months of media blab about how daring and outrageous

the last film by the late Stanley Kubrick would be.

–Rod Dreher, The New York Post

WHAT A WASTE OF MY TIME! It was not entertainment,

and I came out of the film, thinking that I had been hoodwinked in the worst

way, by the media, and the marketing idiots for this piece of ****.

–anonymous poster, on Entertainment

Weekly’s Movie Boards

It SUCKED - BIG TIME. It was laughable.... Sexiest

movie ever–are they serious?

–anonymous poster, on Entertainment

Weekly’s Movie Boards

Owen Gleiberman, Stephen Hunter, and Rod Dreher are not alone

in having completely missed the point of Eyes Wide Shut. Drawn in by the

advertising, audiences all over the United States were expecting to see some sort

of racy thriller. They were disappointed. Over the summer, interactive movie web

sites all over the internet, such as Entertainment Weekly's Movie Boards,

were replete with negative, even hostile, opinions.

Some of the criticisms leveled at Eyes Wide Shut are not unfair. Yes,

Eyes Wide Shut is long, and like many Kubrick films, sometimes exasperatingly

slow. Yes, Eyes Wide Shut is unrealistic, perhaps ridiculously so. As

in other movies, Kubrick doesn’t make much of a distinction between the real

and the surreal, freely mixing both into his narrative. In his explorations

of psychological truths, Kubrick has rarely seen the need to limit himself to

what can be considered “realistic.”

And yes, Kubrick is a little out of touch with contemporary mores and attitudes.

The idea that one's husband or wife may have fantasies about other people is

hardly a shocker nowadays. On the other hand, the view Harford expresses to

his wife before her rambling confession, that women are less likely to be unfaithful

than men because women only feel lust as a function of love and commitment,

is still a pervasive notion. Indeed, Dr. Drew (“a board-certified physician

and an addiction medicine specialist!”) makes this argument nightly on MTV’s

popular Loveline and on the eponymous syndicated radio show, suggesting

that any women deviating from the pattern are dysfunctional and in need of therapy.

Let’s set aside the expectations created by the advertising and investigate

Kubrick’s final work more closely. Let’s not assume that Kubrick intended simply

to make a sexy movie. Alice comments that “one night, or even one lifetime,

cannot reveal the truth.” In the case of Eyes Wide Shut, one cursory

viewing is not enough to reveal all the layers of meaning. Eyes Wide Shut

is not just about sex and obsession. Rather, Kubrick studies the potential destructiveness

of the ennui that can permeate a marriage after nine years. He argues that psychological

unfaithfulness can be just as devastating as literal (physical) unfaithfulness.

And in the end, he comes down on the side of family, commitment, and monogamy.

Enlightened as much of contemporary society

is about sexuality, people know that sexual desire for other people doesn’t

stop with marriage. Even fundamentalist Christians recognize this; in fact,

they even have a word for it: “temptation.” In a healthy marriage, of course,

those sexual impulses become unimportant and not worth pursuing. That doesn’t

mean that they don’t continue to exist. “I may be married, but I’m not dead,”

as the saying goes. So it is not in itself remarkable that Alice has a fantasy

about another man. What upsets Harford, and what would be upsetting to most

men in his place, is not just that Alice has harbored a secret desire for a

stranger; rather, it is how she confesses it, in excruciating detail, and making

it perfectly clear that she was ready to sacrifice her entire marriage if the

sexual interest had been mutual. Most people can relate to how disturbing the

mental image of one's lover with someone else can be.

Moreover, Alice’s confession challenges all of Harford’s assumptions about

women. To Harford, Alice’s willingness to throw herself into another man’s arms

is a betrayal, because women are supposed to experience lust only in the context

of a committed relationship. Aren't they? Men, on the other hand, are biologically

different. Their lust outside of a relationship is insignificant and excusable.

It has nothing to do with love. Or so many men believe.

It’s been said that it’s ludicrous how every woman (and one man) Harford meets

displays sexual interest in him. This strains the story’s credibility, but Kubrick

probably cast Tom Cruise as Harford very intentionally–because it’s at least

somewhat believable that women would throw themselves at him. Also, it's possible

that the women’s reactions to Harford on this particular night are not unusual.

Perhaps Harford is only now noticing how women respond to him, or maybe he is

for the first time seeing their behavior in a different light. It dawns on Harford

that none of these women, not even the hookers, are so different from his wife.

In fact, one of them, Marion (Marie Richardson) is almost exactly like Alice–a

woman in a committed and loving relationship, engaged to be married–and yet

willing to succumb to her desire no matter what the cost.

To Harford, as to many men, women are categorized as either Madonnas or whores.

Alice, the doting wife, personifies all that is good in women, whereas the two

models who flirt with him at Victor Ziegler’s party embody the whores. The Madonnas

are the women you love and respect; the whores are the women you screw and forget

about in the morning. But Harford makes an astonishing discovery during his

night of flirtation with debauchery. The Madonnas have suppressed desires that

are surprisingly carnal, and the whores are terrifyingly human.

Harford’s journey of discovery begins when Ziegler (Sidney Pollack) asks him

to treat a prostitute for a drug overdose. Without his medical tools, Harford

must revive her by gently shaking her and calling her name. Unable to treat

the flawless naked body lying in front of him, Harford must reach out to the

woman’s soul in order to save her. Harford probably never has had a prostitute

among his high society clientele, but there she is, as human and vulnerable

as anybody else–in fact, more so. Perhaps Harford has never before seen a woman

like her as a victim. In contrast, Ziegler’s callousness is chilling–he is only

concerned about the inconvenience of having a dead hooker in his house. Later,

Ziegler casually refers to her as “you know, the girl with the nice tits,” objectifying

her even after death. He does not see her as a person, nor does he care to try.

Later, Alice’s and Marion’s confessions send Harford out into the streets in

a state of confusion. His night then becomes a tour of objectified women, from

Domino (Vinessa Shaw), an uncommonly beautiful streetwalker, to an underage

girl (Leelee Sobieski) being pimped by her father (Rade Serbedzija) at the costume

shop, and finally to the naked, faceless women at the center of the bizarre

ritualistic sex in the private club, in which they are used by faceless men

for the entertainment of other faceless men.

The surreal orgy has been a lighting rod for the movie’s detractors. Apparently

its transgression is that it is misogynist and absurd. To those who complain

that the scene is sexist, I say, “Exactly!” It cannot be taken at face value.

It is a metaphor for total masculine control over sexuality and an extreme expression

of the basic subconscious attitude of many men toward women. The orgy’s male

participants are New York’s elite–men with power and money–and the women are

high-class prostitutes. The men have used their power and money to create the

ultimate male fantasy–a environment where subservient females are reduced to

sexual instruments. The orgy may not be the average man’s literal fantasy, but

it is an extension of the traditional male outlook toward women and sexuality.

As such, Kubrick did not intend for the orgy to arouse us. Kubrick intended

to horrify us.

The critics are right: Eyes Wide Shut isn’t erotic at all. With the

exception of the flirting at Ziegler’s party early in the movie, the film's

depiction of sexuality is downright macabre. The women aren’t sensual and desirable;

they are walking corpses. Used and casually discarded, they die brutally, unmourned.

And yet, the women are more human than the men. All of them–the wives and the

whores–have emotions and desires stifled in a cold, male-dominated world. Kubrick

strips away the allure of men’s sex fantasies and shows the stark truth underneath.

Similarly, when Harford learns that many of the orgy’s participants are the

same people who were at Ziegler’s Christmas party, Kubrick is once again saying

that a harsh reality lurks underneath everything we think we know.

The orgy is a revelation to Dr. Harford, but not the one he expects. Instead

of liberation and pleasure, he finds confinement and pain. Even with the opportunity

to have sex with a beautiful woman with no strings attached, he seeks her identity.

An anonymous sexual tryst is not really what Dr. Harford is looking for.

The next day, after desperate attempts to discover the fates of the piano player

Nick Nightingale (Todd Field) or the woman who interceded on his behalf at the

orgy, Harford returns to Domino’s apartment. It is an attempt to return to a

sexual situation where he is in control. He is looking for reassurance after

his wife’s confession and his experience at the mansion. What he finds instead,

when he learns that Domino is HIV-positive, is another brush with death, another

example of the victimization of women, and another demonstration that what meets

the eye doesn’t necessarily comport with the reality underneath. Domino is the

perfect sex partner, willing and beautiful... or is she?

Harford’s attitudes toward women have nearly made him a victim, too. A victim

of an unfaithful wife, a victim of HIV, a victim of an unknown fate at the orgy.

Like the women he meets, Dr. Harford is himself objectified by those who throw

themselves at him or take his money. Repeatedly opening his wallet, Harford

assumes that every human interaction is a transaction and that all people have

their price. He dismisses the god-like image that doctors have, and yet he uses

that image when it’s convenient. He keeps flashing his medical credentials to

get what he wants, to the point of absurdity. But by the end of his journey,

Harford has seen the results of treating people like commodities to be used

or bartered.

When Harford returns home to find Alice with the mask from his costume, he

is unveiled. His horror at having risked everything that he loved for the sake

of a prurient diversion is devastating. He does not lie, however. He confesses

and asks Alice for her forgiveness, who earlier has confessed a dream that parallels

Harford's journey. Now, they can continue with their marriage, without any masks,

with their eyes wide open. Their newly-found knowledge may be painful, but their

marriage, Kubrick suggests in the abruptly truncated final scene, will in the

long run be made stronger.

AboutFilm.Com

The Big Picture

|

| Alison |

-

|

| Carlo |

A-

|

| Dana |

A-

|

| Jeff |

B+

|

| Kris |

B

|

| ratings explained |

Eyes Wide Shut is a largely visual work. The languid scenes at Ziegler’s

party float along sensuously. The orgy, except for its post-hoc digital fig

leaves, is an eerie visual masterpiece, with its monstrously carnal masks and

garish colors. Every shot is painstakingly composed. Even the street signs comment

on the story–one on the back exit of the jazz club where Harford meets Nightingale

reads “All Exits Are Final.” The primary function of language is to enhance

a mood. The words are frequently simple and repetitive, and yet musical, like

Hal’s cadences in 2001: A Space Odyssey.

In Eyes Wide Shut, Harford speaks deliberately, often repeating himself.

He is in a daze, waking up from a lifetime of comfortable assumptions. The stilted

dialogue adds to the feeling of confinement and disquiet.

Tragically, Eyes Wide Shut does have an Achilles heel. Functioning almost

exclusively on the visual and emotional level means that Eyes Wide Shut

is not plot-driven. This is not necessarily a problem per se (see, e.g.,

Wings of Desire), but in Eyes Wide Shut the narrative doesn’t

flow smoothly or coherently. It stops and starts; it meanders; it doesn’t seem

to be going anywhere. Because Kubrick loses the narrative thread sometimes,

Harford’s psychological breakdown is not presented as powerfully and cohesively

as it could be. Instead of one event propelling him to the next, Harford’s activities

seem random. He wanders around, and things happen to him.

The film’s narrative problems might not have existed had Kubrick not died.

The movie is touted as Kubrick’s “final” cut, but Kubrick had a habit of whittling

away at a film until days before its premiere. It’s entirely possible–even likely–that

Kubrick would have removed another ten or fifteen minutes of footage, which

might have improved the flow. But part of the blame must also go to Tom Cruise.

While Nicole Kidman is brilliant, hers is only a supporting role, and Cruise

turns in a performance that is barely adequate. He is by no means a terrible

actor, but he’s not a sufficiently nuanced performer for this role. He can only

show Harford's inner turbulence in the broadest way.

I cannot shake the impression that Kubrick has played a huge joke on us all.

Kubrick, who had final say in all the marketing and promotion of the film, advertised

Eyes Wide Shut as a seductive thriller. One of the trailers he submitted

to the studio consisted only of a long shot of Cruise and Kidman semi-clothed

and kissing, with Kidman staring at herself in the mirror all the while. Kubrick

knew what would draw audiences to his movie–exactly the same things that draw

Harford deeper into his exploration of forbidden sex, the orgy in particular.

The voyeur within us. The promise of illicit licentiousness. And Kubrick delivers

on his promises. But, instead of being titillated, audiences were left angry

and confused. Just like Harford. A powerful way to make a point, wouldn’t you

say? Somewhere, Kubrick is laughing from beyond the grave.

Review

© September 1999 by AboutFilm.Com and the author.

Images © 1999 Warner Bros.