My phone call wakes Voss the next morning, so he calls me back after taking

twenty minutes to pull his brain together. We kick around the names of a few

establishments and meet an hour later. In person, the forty-year-old Voss looks

like he could be a character from one of his films, with a large tattoo on one

arm and black-and-white clothes that might be described as "rock-and-roll casual,"

except that "rock-and-roll" doesn't quite fit with a Starbucks in Brentwood.

Voss's flexibility in meeting me is not surprising. He embodies the independent

spirit and do-it-yourself filmmaking ethic. In 1987, after graduating from UCLA

film school, Voss co-wrote and co-directed Border Radio with frequent

collaborator and former classmate Allison Anders (Gas Food Lodging, Mi Vida

Loca). The shoestring-budget movie about three desperate L.A. punk musicians

who steal money and flee to Mexico didn't make an impact, and the next few years

found Voss dabbling in both directing and screenwriting. Bills have to be paid,

however, so in the '90s, Voss directed a string of straight-to-video genre pictures

such as Poison Ivy: The New Seduction, Below Utopia (later renamed Body

Count), and The Heist. Yet Kurt often found ways to work with musicians

in them, such as Ice-T, John Doe of X, and Michael Des Barres of Power Station.

In 1998, as the straight-to-video/cable market for action movies began sputtering,

Voss reconnected with Anders, both of them resolved to rediscover their filmmaking

roots. They conceived a film about aging rock-and-rollers that unfolds along

multiple storylines. Determined to shoot right away, they wrote the script in

just a couple weeks and recruited a cast whose real lives paralleled those of

their characters. They included Rosanna Arquette, Ally Sheedy, Beverly D'Angelo,

and many actual musicians such as John Taylor (Duran Duran, Power Station),

John Doe, Michael Des Barres, and Martin Kemp (Spandau Ballet).

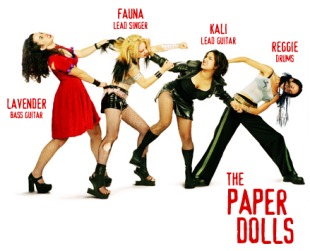

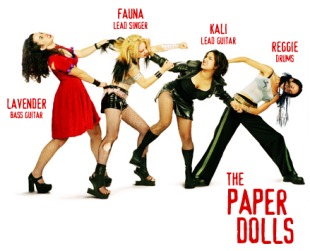

As with many of Kurt's films, the cast is populated with real-life rockers--the

four leads are all musicians and Poledouris, daughter of renowned film composer

Basil Poledouris (Conan the Barbarian,

The Hunt for Red October), wrote the film's music, having already worked

on a score for John Waters (Cecil B. Demented). Other musicians include

Coyote Shivers as the object of two of the Dolls' desire, and Janis Tanaka of

L7, Inger Lorre of the Nymphs, and Lemmy Kilmister of MotŲrhead among the Paper

Dolls' hangers-on. With the same do-it-yourself aesthetic and real-world absurdities

that characterized Sugar Town, Dolls is everything that most bigger-budget

rock-and-roll movies aren't--both authentic and amusing.

AboutFilm: Obviously you have a film background; you went UCLA film

school. What's the music connection? How do you know all these musicians;

how is it that you're interested in musical themes?

Voss: I don't know, just a rock fan from adolescence really. It's

almost like a religion--a secular one, of course. John, Paul, George, and

Ringo were the gods on my wall when I was a little kid. I just always loved

pop music, and then English punk. 'Around '78 or '79 I got really into that,

at the end of the Pistols. At the same the LA punk scene started to happen,

and that's what Border Radio grew out of. I guess it was about '81

when I met Allison. We were both going to Valley College. Allison had just

come back to the Valley after having lived there several years earlier. I

was a high school dropout, and her second daughter was just old enough to

go back to day care. She was big into punk rock, the LA punk scene, so she

introduced me to some of those bands--I was following the English stuff. Out

of our interest in LA punk came Border Radio, later, when we eventually

got into UCLA and decided to make a feature.

AF: I'd like to backtrack over your career, but let's start with your

current movie, Down and Out with the Dolls. How did you meet the four

leads and the other musicians involved in this movie?

Voss: It was just a very diligent casting process that led us eventually

to the players. We did a lot of open casting, in the Pacific Northwest primarily.

AF: So you always knew that you wanted to make it up in Portland?

Voss: Always had that in mind. Ideally I wanted to use all local players,

or at least people exclusively from there and Seattle, but we ended up bringing

in a couple of people. Kinnie Starr came in from Canada, and ZoŽ Poledouris

came in from LA.

AF: And Coyote Shivers, also.

Voss: Coyote also came in from LA, that's right. You would think with

all the musicians in Portland we would have had it absolutely surrounded,

but it didn't work out totally that way. So they were all fresh faces, not

just to me. Most of them hadn't acted at all. Nicole Barrett, who plays Kali,

and Melody Moore who plays Lavender, were both 19 or so when we filmed. They

had done a little high school theater or something, maybe.

AF: When did you film, exactly?

Voss: End of 2000.

AF: Did you put this together as quickly as you did Sugar Town?

I understand that movie was six months from conception to finish.

Voss: Yeah, about that fast, although getting it to the marketplace

turned out to be a longer haul, a bigger proposition, for a number of reasons.

Number one, no cast--no names to speak of--always poses a greater challenge.

And, of course, the industry is just in total, utter turmoil. I don't know

where it's going to land, what's going to happen to the independent thing.

I don't know who's going to even afford to make little movies as an ongoing

proposition.

AF: Were you trying to get a studio or distributor attached beforehand,

or did you want to finish the product first?

Voss: Yeah, the idea was to finish the product first, as was the case

with Sugar Town, to strike fast. In that case we sold the film to Film

Four, and they paid for the whole thing. But we still retained the U.S. rights,

which turned out to be financially quite a good deal for us, for a change.

But, similarly, in that case, we didn't know where we were going to land with

it.

AF: What was your budget for Dolls and for Sugar Town?

Voss: Sugar Town was under four hundred thousand dollars, and

Dolls was not terribly far off.

AF: How did you fund it?

Voss: Dolls was financed by an Australian company called White

House. I actually got to know the heads of the company on a previous straight-to-video

title I did called The Heist, which was a shoot-'em-up thing with Ice-T

and Luke Perry. They were investors on that film, and we became friendly and

decided to work on something a little more quirky.

AF: Did you originate the concept for Dolls completely on your

own or did you collaborate?

Voss: No, I collaborated with [co-writer and production designer]

Nalini Cheriel, who had performed in several bands up in that part of the

world in the '90s. It was really out of her anecdotal stories, just funny

shit she told me about the indignities of life on the road, and cohabitation

with other musicians and related stuff that suggested the movie.

AF: With real musicians and real experiences influencing the film,

it had a very natural feel, I thought. That's obviously something you were

conscious of as you worked on it?

Voss: Right, we were quite intent on that, and similarly, to make

the girls not only plausible players, but to make sure they didn't look like

a Coyote Ugly-type rock band. They seem like real girls from that part

of the world.

AF: In Dolls, Fauna [played by ZoŽ Poledouris] seems to be

cut from the same cloth as some of the characters in Sugar Town. Ambition,

desperation, and desire for fame all wrapped into the same person. Is that

a character you find particularly interesting?

Voss: Well, in the case of Dolls, it's de rigeur to

have the bitch-on-wheels singer, and obviously it's a clichť because it's

such a pervasive truth. In Sugar Town, the character of Gwen [played

by Jade Gordon]--I don't know, we were thinking of almost a Courtney Love

type of person, as our inspiration--someone who is totally dedicated to the

idea of success at any and all costs.

AF: Well, Gwen's a sociopath; I wouldn't call Fauna a sociopath.

Voss: Absolutely. If Fauna were as purely calculating as Gwen, then

the band wouldn't implode. So yeah, I agree, she's not quite as much a sociopath.

AF: You chose Melody's character, Lavender, as sort of the point-of-view

of the film. Is that because she was caught in the middle and had less of

her own drama?

Voss: Yeah, it's a little bit of that. She's supposed to be the straighter

one, if you will. A certain segment of the audience will relate to her a little

more easily.

AF: In Sugar Town, you worked with veteran musicians, whereas

in Dolls, though have some supporting players who are veterans, you're

primarily working with people who are fairly new on the scene. What was the

difference in working with them?

Voss: Well, one big difference was that they didn't have the relationship

with the camera that someone like John Taylor has, who was in Duran Duran

and photographed probably a million times. Someone like that knows instinctively

where the lens is. Ice-T is another guy who comes to mind who has done so

many movies that you say, "Hey, Ice, walk backwards across the camera track,

pivot, find your light, and shoot the gun," and he'll do it in the first take.

It was difficult sometimes for these people to walk and act at the same time.

Having been in front of the camera just a couple of times, I'm empathetic,

because it's very disconcerting. Someone shuffles you off to the trailer;

you sit there for eleven hours wondering what the hell's going on. Then someone

comes and drags you in front of the camera, and they're already saying, "Okay,

we got it. Moving on." You get one or two takes. So it's a tough job.

And it was good in a way, it forced me to reconsider some of my tricks, my

ways of covering action. I'm used to doing a lot of dolly tracks. We were

using a dolly track, for instance; you turn around with the same track and

film the other side of the room, and a lot of those tricks didn't work in

this case. I had to be a little more seat-of-the-pants to accommodate the

players.

AF: I guess when you film one side of the room and then the other,

you have to make sure people hit the exact same marks, otherwise it doesn't

look right.

Voss: Right. Just the math of it, the geometry of it all was really

wigging some of them out when we started filming. I remember Kinnie Starr,

the drummer, saying as actors do, "My character would walk over here and then

go stand over here," not realizing this choice she made at 8:30 in rehearsal

that morning [would mean that at] 3:30, we'd go, "Okay, now we [need] the

little piece of film where she crossed to here and back again." Suddenly you've

broken the whole thing into thirty shots, and they're ready to cry. So, yeah,

I started trying to get people a big wide frame to wander around in, that

kind of stuff.

AF: You shot in digital video. Was that helpful with that kind of

thing, in addition to being cheaper?

Voss: Yeah, it's helpful in terms of being able to do more with choice.

That's the main benefit. The downside was that, having never worked with it

before, I was dubious that it would ever look like a movie. You have to use

a lot of light and achieve a lot of contrast for the transfer. When you're

shooting interiors with white walls and a lot of light, it looks like a sitcom

on video. It looked like we were doing Who's the Boss?. You look at

the dailies and go, "whoa."

AF: I've seen digital video movies that are of wildly different visual

quality. Sometimes they look very pristine and other times they look very

muddy. It has to do with the lighting?

Voss: Yeah, I think that's largely it.

AF: So these were small-budget films. What's the biggest budget you've

ever had to work with?

Voss: Two million dollars, maybe. Baja was around two million

dollars. Yeah, we're really small fish, especially nowadays. I really don't

know where the independent fits in anymore when twenty-five million dollar

movies are considered straight-to-video fare. We're like penny postage stamps.

AF: Have you ever been offered a major studio film? Would you do one?

Voss: Sure, why not? I'd direct a James Bond movie or something. It

hasn't been the case of preserving my integrity. I've just never had the opportunity.

I wouldn't want to put myself up for something that I didn't think I could

do a good job on. I wouldn't to direct material I didn't feel I could serve,

but I don't have anything against doing bigger pictures.

AF: Of course, the more money and the bigger the picture, the less

freedom you probably have.

Voss: That's the trade-off, I suppose. But the other way around is

you can have a lot of control and an infinitesimal audience, or no audience

at all.

AF: How widely is Dolls going to be released initially?

Voss: I think twelve cities the opening weekend, and the rollout from

there will probably depend on who comes out to see it. The film succeeding

depends to a certain degree on people going to see it for the more universal

aspects, which I think are there. Women in their fifties at European film

festivals have come up to me and said, "You know, it reminds me of when of

lived in a squat." Hopefully we can reach some non-rock fans.

AF: I'd like to talk a little bit about the music of the movie. ZoŽ

was the primary composer. The only composer?

|

|

The Fighting

Dolls

|

Voss: She was. She wrote the underscore and she wrote all of the Paper

Dolls songs.

AF: Did she write Kinnie's lyrics? Or did you?

Voss: The corny ones? I didn't write those. You know who wrote those?

Jeff McDonald from Redd Kross. In Sugar Town he plays the junkie who

Gwen leaves to die. He's a very good pop writer, very funny. All we gave him

was the set-up, and he wrote her lyrics based on that. But Kinnie writes her

own very earnest little folk songs, so she could have written her own version.

AF: So how did the music come together? How was it developed?

Voss: We had a music supervisor named Howard Paar. I hadn't worked

with Howard before--I've worked with him subsequently--and Howard knew of

ZoŽ. She had done a John Waters movie [Cecil B. Demented]. Originally

we were just talking to her about the score, but then we screen tested her

as well. We liked her very much. She really understood the world. She had

been with a girl rock band, though she hadn't lived with one. She's more of

a Hollywood kid, in fact. And then, in terms of the texture of the band's

music and stuff, ZoŽ knew we wanted it to sound plausible that a twenty-year-old

four-piece band would play this stuff. They, in fact, can play all that stuff

together.

AF: So they all played their own instruments in the film.

Voss: Yeah, well, they're playing the playback. The music isn't live.

But they recorded the basic tracks. They recorded those in ZoŽ's hotel room

while we were doing the film. I'm very happy with the music, and I'd love

to work with ZoŽ again.

AF: What kind of challenges did you run into when you began shooting?

Did anything go unexpectedly wrong?

Voss: Not beyond the usual. We were shooting in Portland, so it rained

all the time. That posed the usual continuity headaches, especially in the

beginning when they're having a barbecue and running around and so forth,

trying to figure out how you're going to deal with the wet sidewalk in one

shot. It's amazing that Citizen Kane type movies get made. How do they

get it so right? But no, no huge production tales. Though Lemmy [bassist and

singer for MotŲrhead, former roadie for Jimi Hendrix] was quite an adventure.

Lemmy Kilmister, he's such a beast.

AF: I assume he's slightly more coherent in real life than he sounds

in the film.

Voss: Mm, no, not terribly so. Actually he's quite bright, but he's

surreal.

AF: So was he being himself? The personas in Sugar Town seemed

to be very close to the musicians themselves. Was that also the case in Dolls?

Voss: In the case of Sugar Town, we actually cast before we

wrote the script, so we were quite consciously playing with the actors' personas.

In this case it was just a matter of casting close to the bone, you know,

including casting Lemmy as a speed freak.

He was actually based on a guy I knew as an adolescent. He was renting a

walk-in closet. He was a guy in his twenties. Me and the other little suburban

mallrats I ran with idealized this guy. We all thought he was really interesting

because he lived in closets. But again, that's the sort of thing you would

find in Portland. A lot of people live with no apparent means of support.

I kind of envy the musicians up there. You're down here, busting your ass

in Hollywood, and it's like Lily Tomlin's joke about the rat race--all you

prove in the end is that you're a rat. These kids, even people in their thirties,

they live out there for ten thousand dollars a year or something. They've

got a band; they've got a girlfriend; they've got a two-hundred-dollar car.

Their friends are all waiters; they all eat for free. They got it wired.

AF: What are some of your favorite rock-and-roll movies by other people?

Voss: Oh god, my favorite rock and roll movies? I haven't seen it

in years--I liked Phantom of the Paradise a whole lot; it's real corny.

It's a Brian de Palma movie. Its pedigree is a little dubious--it's got a

rock score by Paul Williams--but it's very pop; it's good in that respect.

I don't know, I think Abel Ferrara's stuff actually qualifies as rock and

roll. It's got an anarchic spirit even when it's not dealing with it in terms

of the subject matter. I wish I had Allison here to jog my memory. She's teaching

a class in rock films at UCSB. We just showed Dolls up there about

a week ago. She had Michael Apted there Friday to show Stardust, I

think, from the '70s.

AF: I'd like to go over your filmography now. Could you tell me a

little something about each film--maybe something that sticks out or how you

remember the film in your head? Let's start with your first movie with Allison

and your first movie overall, Border Radio.

Voss: I saw it again recently because I transferred it--made a new

digital master.

AF: Is it coming to DVD?

Voss: It was supposed to come out with Sugar Town. I worked

on this project for about eight months for no pay, including getting all the

releases from Sugar Town performers. To put restored or omitted scenes

on the disk, you gotta get a new release. There's no one at these companies

who does this; they kick it back to the producers. So anyway, I spent a long

time on this. The whole thing was ready to go, and then USA Entertainment

got bought by Universal, who promptly shelved the project. Universal wouldn't

even call me back about it. It's indefinitely in limbo.

AF: I'm sorry to hear that. Was it released on video at all?

Voss: It was, it was released at Blockbuster, as a 'Premiere.' We

heard subsequently from Universal--their official explanation was that films

released in that manner don't do so well in sell-through. Whether that means

anything or not, I don't know. In any case, having seen Border Radio

recently, it's a total shaggy-dog story. Barely coherent plot, but very nice

to look at. It's shot in glimmering black and white by Dean Lent, who subsequently

shot Gas Food Lodging for Allison and Genuine Risk for me.

AF: And you worked with John Doe.

Voss: Yeah, it featured John and The Blasters, so it had people from

the punk bands. And Allison and I think that, though we've obviously learned

our trade since making it, we've also lost something, maybe. There's some

really beautiful shots in it. We'd spend half a day waiting for the sun. David

Lean, you know. Stuff that you can't do when you have a six-page schedule

on the day, which is what moviemaking ultimately became for usÖ I don't know,

it's an interesting little curio, and it definitely captures the L.A. punk

scene in the '80s.

AF: Next was Genuine Risk [1990].

Voss: Genuine Risk was a movie with Peter Berg and Terence

Stamp that was done as part of the noir wave of the time. Actually

a better example of the genre was Delusion [1991], which I was a writer

on. But Genuine Risk had some good stuff in it, too. I really liked

working with Terence Stamp, because he's so economical an actor.

AF: Horseplayer [1991] with Brad Dourif.

Voss: Horseplayer was made very inexpensively around the same

time and ended up at Sundance. I ended up marrying Sammi Davis [Hope and

Glory], who acted in it. We were married for a few years. I've just seen

her again this past year. She moved to the Midlands and has left the business

pretty much. But I went up there to talk about doing a new film together.

I think we're going to work with the writer David Birke, who co-wrote Horseplayer,

and re-activate that whole team. I'm developing a script for her that's based

on a short I wrote that I was going to do last year with Katrin Cartlidge

before she died. She was in Naked, the Mike Leigh movie. I think From

Hell was her final movie. A brilliant, strange, gawky woman. I was really

looking forward to working with her. She was going to play an artist based

on Tracey Emin, a contemporary conceptual artist in London. Anyway, Katrin

got ill and died this past fall--41 years old. It was quite shocking. So anyway,

I'm taking the character out of that short to develop a feature.

AF: Is that what's next for you?

Voss: Maybe. There's four or five things juggling. There's something

to be said for just sticking to one project and being very kamikaze, but in

this climate you've gotta have a couple of things going because everything

is so apt to crash and burn. Ideally, that would be next.

AF: Okay, Baha in 1995.

Voss: Yeah, Baha was several years later. I had a couple of

lean years in between. Where the Day Takes You came out in '92, which

I wrote, and Dangerous Touch in '94, which I also wrote, a straight-to-video

thing. I think Allison and I were selling stuff in the recycler in '93. Baha

was a movie I did with Molly Ringwald, Lance Henriksen, and Donal Logue. It

was a lot of fun to make. We shot out on the Salton Sea, south of Palm Springs.

On a budget it was a challenge to re-create Mexico. For example, there's a

hotel opposite a strip mall, but I wanted to make it appear that it was next

to a body of water, so I shot all the reverses at the Salton Sea two weeks

later, that kind of thing. I like that part of filmmaking, all the jigsaw

puzzle stuff. I don't know, it's got some virtues. I think Lance Henriksen

gives a very good performance.

AF: One of the Poison Ivy movies was next [Poison Ivy: The

New Seduction (1997)].

Voss: I don't know. I needed a paycheck, and I knew it would recoup

its costs. I liked all those kids very much. It's nice working with really

young kids because they don't know--I just told them to stand there and do

what they're told, and they did it. That movie was made for well under a million

dollars. I should sue New Line because it's a perennial seller, and they've

never paid me a nickel in royalties. For how little money we made it for,

I thought it was a pretty slick-looking product, which came down to that photographer,

a lot of it--a very good DP [Feliks Parnell], who I'd like to work with again.

AF: The interesting thing about these straight-to-video movies is

that they do make a profit. They have a certain budget, five hundred thousand

to a million dollars, and they're expected to recoup. They tend to do well

in international sales, like on cable in Asia.

Voss: Well, they always have, and that's the problem. It's not happening

now. Roundabout '97, the Asian market collapsed for action movies. And now

I think part of the problem is all the DV films. There's more movies now than

ever, and competition for the entertainment dollar. These movies aren't recouping

the way they used to. These little producers used to make something for a

million, and get on a roll. One would finance the next. They crap out eventually,

but then they go start a new company. But these guys just aren't getting to

first base.

The buyer for USA Home Entertainment before they were bought by Universal

was bragging to me--it was like a big fish bragging about eating little fish

before he himself was swallowed--he was saying he was getting all these straight-to-video

films for no advance at all to the producers, just part of the profit. Two,

three million dollar movies that would have two or three solid names for the

video box. There's no cash flow in that, if the producer has to wait not only

two years after the movie is finished, but another six months for the video

to ship. And it's always been the sort of business where you're betting dollars

to make nickels. Slim profit margins. Sex Lies and Videotape once every

hundred times at bat. On average it's a grind-it-out proposition. And now

I think these poor guys are really hurting.

AF: Amnesia [1997]?

Voss: AmnesiaÖ who was in that? A bunch of nutters. [laughs]

Sally Kirkland, John SavageÖ Ally Sheedy and Nicholas Walker both ended up

appearing in Sugar Town. This was a quirky little movie. It was a TV

premiere on Showtime. It got some good notices. They called it housebroken

David Lynch. It was a noir thing, but it got progressively stranger.

It was a tongue-in-cheek little movie. I liked that one.

AF: Below Utopia, renamed Body Count [1997], with Ice-T,

Alyssa Milano, and Justin Theroux.

Voss: That was the first of the two times I worked with Ice-T. All

good people, quite an enjoyable shoot. It deals with a home invasion, and

so you spend a lot of time with the protagonists hiding in the unlit basement

waiting for the other shoe to drop, so it had kind of radio-play elements

to it. Pretty solid little thriller. I think it was a budget of about a million

dollars.

AF: Okay, The Pass, aka Highway Hitcher [1998], with

William Forsythe, Elizabeth PeŮa, and James LeGros.

Voss: Not a movie I have really any fondness for. William Forsythe

plays a guy who has a midlife crisis and he's reinvigorated by an incident

he has while he's on the road to Reno. I don't know, it was a little too schematic.

A bit of a misfire. And I loathe William Forsythe. He's a total fucking

prick. And that you can print. There's something with actors in their 40s,

I don't know--there's this tendency with these guys, either they're not where

they wanted to be, or--I mean, this guy was making good money and working

a lot. It's almost like they have a bad conscience about the job, like it's

unmanly or something, so they try to compensate by busting the director's

balls 24/7.

I had heard terrible things about this guy taking over people's shows, essentially.

Alex Rockwell did a movie with him [Sons]. Apparently he just hijacked

the movie. It's just unpleasant to deal with a guy like that. Really contentious

and petulant. Ö James LeGros is a lovely guy, but by his own admission he

was miscast, because he's supposed to be quite scary, and he told me afterwards,

"Ah, it never works." I kind of had a sinking feeling even during the table

readings that there was something not quite right. But again, I had no money,

I was down to my last five hundred bucks. That was the cast that worked for

the producers, so you had to hold your nose and proceed.

AF: Which brings us up to Sugar Town. It sounds like after

some paycheck movies that Sugar Town really was a reconnection with

some of the things you were passionate about.

Voss: It was. For Allison, too, it was a necessary return to that

stuff. Stuff she was developing with the studios just wasn't advancing. We

made Sugar Town to combine our strengths and our resources at that

point. I should say, too, going back to what I said earlier, the Asian action

market had fallen apart at that point. Sugar Town's distribution ultimately

got screwed up, because it was bought up by October, who were then bought

by USA immediately. Then when it came time for USA to release the DVD, the

home entertainment side wanted to rectify the poor treatment on the theatrical

front, but they were bought by Universal and are now Focus. But financially,

it improbably turned out to be quite a payday for us.

AF: One of our writers reviewed Sugar

Town quite positively, but her one complaint of it was that she didn't

get to spend enough time with the characters. It was only ninety minutes.

She wanted to get to know them even more. What do you think hearing that?

Could there have been more movie?

Voss: We only had 18 days to shoot the thing. We just didn't have

the resources to make the story any longer. I don't really take that as a

criticism, in fact, it's a compliment. It's nice that she felt that way. But

I think there was just enough of the movie. We had a two-hour cut at one point.

There was a little bit more time spent at John Doe's house, a couple more

scenes with the wife, but nothing that really advanced the plot. We had to

pace it out to make sure the first act break occurred where it did. It needed

to have that to keep rolling. So no, there wasn't really too much more movie.

A couple of funny outtakes though. There was a funny bit with Michael Des

Barres screwing Beverly D'Angelo--

AF: Yeah, we didn't see the actual sex scene.

Voss: Right. And she's telling him that he should ditch the band,

and I think she's promising she's got a contact to get him a solo recording

contract. This is the thing that gets him off ultimately. It was a funny little

bit, but it was too off-the-wall for the movie. The other scene is very gentle.

It just proved redundant and breaks the tone.

AF: Then after that you did The Heist [1999], which was another

action movie.

Voss: Yeah, that was something I'd committed to before Sugar Town.

It just took awhile for the money to come together. That was a crazy movie.

I had a producer on it who was trying to get around paying certain deposits

to SAG. SAG came and shut us down, and took all my actors away. I was shooting

close-ups with the script girl's hands for inserts, anything to make it work.

It's an armored-car heist movie. An armored car gets jacked. So then we sent

the armored car out to do some running shots, second-unit-type shots. We had

one of the guys from the camera crew, a black guy who was dressed to double

as Ice-T. He had a bandana on, and some stage blood to match an earlier scene.

There was also stage blood on the window of this armored car, and when they

stop to refuel it, some good Samaritan puts two and two together. Next thing

we know SWAT was mobilized. SWAT actually surrounded these guys on the 6th

Street bridge. Helicopters, police cars, the whole thing. The guys are lucky

they weren't shot, because apparently they came out brandishing their walkie-talkies

to prove they were a movie crew. That whole movie was like that. De'aundre

Bonds was in that, playing the third member of Ice-T's crew. I just got a

call from Patrick Goldstein from the L.A. Times who wanted a quote

because De'aundre is in prison for twelve years for murder. He stabbed his

aunt's boyfriend to death. He wasn't violent when we shot, but he was a pretty

live wire. I don't know, that whole shoot was just nutty. But it's a pretty

solid little genre movie. Probably of all those I'm proudest of it, because

it was so hard to make, and it holds together pretty well. I like Richmond

Arquette a lot; I've worked with him a lot and would like to do so again.

AF: Then you co-wrote Things Behind the Sun [2001], again with

Allison.

Voss: Right. Actually the script for that went back to '96, I think.

I was spending a lot of time in Mexico City. Allison and I met in El Paso,

and laid out the story, which is pretty much based on her own rape as a teenager.

So, quite autobiographical. In fact, she went back and filmed the rape at

the very house she had been raped at thirty years earlier. I went down to

Mexico City with the outline and wrote the script in a hotel room down there

over the course of a couple of months. It was kind of like almost like channeling

Allison a little bit. It was a moving experience, actually, to write.

AF: I would imagine it was good to collaborate, if it was really personal

for her. I imagine there were times she needed a more objective, detached

person.

Voss: Yeah, absolutely. I think specifically what I was most able

to provide was--the movie treats the guys, even the rapists, with a certain

amount of empathy and tries to understand them. I think, by her own admission,

that she couldn't have made that leap without someone to mediate to a certain

extent. But yeah, that's a good film. It took ages to get made. Winona Ryder

was supposed to star for awhile, then Heather Graham was supposed to star.

They had these names attached, and they would sit around at studio level awaiting

development. I kept telling these guys, you have to come back to this. I thought

it was going to win some sort of award., I just had a feeling. It did, in

fact, win a Peabody ultimately, which was a trip.

AF: And now, Down and Out with the Dolls. You didn't work with

Allison on this film. What kind of working relationship do you have? You seem

to go away from it and come back to it every once in awhile, and have maintained

that for a long time.

Voss: Yeah, in addition to the stuff we've had produced, we wrote

a spec script on Darby Crash of the LA punk band The Germs. It was about '91

that we did that. It's still kicking around; I think HBO or Showtime are looking

at it at the moment. Madonna was actually going to make, or announced it for

Maverick at one point, though it was probably just for the sake of that day's

publicity. River Phoenix was interested in starring in it at one point. That

isn't going to happen either. We're talking about trying doing something else.

We wanted to perhaps develop a TV show for Don Cheadle, who was so good in

Things Behind the Sun. We have an idea for that. We'll probably take

that out with us this pitch season, which is coming upon us.

And that was it. I couldn't think of anything else to ask and didn't have a

big tie-everything-up-with-a-bow type question prepared. So I asked Voss if

there was anything he wished I had asked him that I hadn't. There wasn't. He

asked me if I had any leading questions I might want to ask. I didn't. So he

inquired about the history of AboutFilm and revealed that he had once written

for Film Threat. After that we went our separate ways. I left making

a mental note to find a copy of Things Behind the Sun and hoping to see

more from Voss in the future--perhaps even interview him again, though next

time in a more contextually appropriate location than a corporate latte outlet

in O.J.'s old neighborhood.